Narrative Strategies of the Vietnam War Coverage by German War Photographer Horst Faas

from 1964 - 1971

–

An analysis of four selected pictures

by Anton J. Hansen

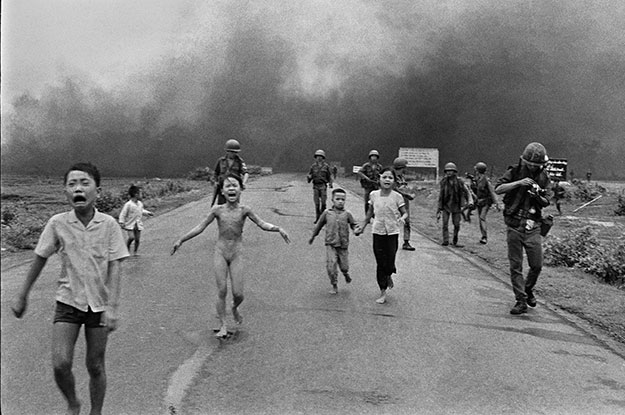

It’s the early morning of June 5th, 1972 and Huỳnh Công Út, professionally known as Nick Ut, joins a team of journalists, photographers and soldiers towards Trang Bang. The village is located about 25 miles northwest of Saigon and heavy fighting has been going on for a couple of days. Nick, only 21 years old at this time, is armed. Not with a rifle, but with a tool that plays an important role in ending this war. A war which has killed more than two million Vietnamese civilians, more than one million Vietnamese soldiers and more than 58 000 US-American soldiers (Lewy, 1980; Spector, 2020). A war, which has left millions traumatized. Since Vietnam gained its independence in 1946, it constantly had martial conflicts with its former colonizers France, and the United States of America which tried to set up a deeply corrupted regime in South Vietnam (Bradley, 2009, p.118). When Ho Chi Minh, the leading politician of North Vietnam who dreamed of reuniting his mother country, started to increase the political and martial pressure on South Vietnam, the United States of America started to send more and more military personnel to South Vietnam. Ho Chi Minh, who was looking for support by the United States, shortly after Vietnams independence in 1946, was rejected by the USA due to its diplomatic ties with former colonizing power France (Lawrence, 2008, p.27). Therefore, Ho Chi Minh switched sides and found the Soviet Union and China as allies. Fearing that Vietnam would reunite and become a Communistic country, which would pressure American alleys in South East Asia, including Cambodia, Malaysia, Taiwan and Thailand, the United States increased their military engagement in South Vietnam in 1964 (Bradley, 2009, p.109). In 1968 already, more than 500.000 US-American soldiers fought one of the bloodiest, most brutal wars of the 20st century. Furthermore, three times the number of bombs were dropped by the USA until 1975 on that tiny South East Asian nation than were dropped by all parties in World War II combined (Bradley, 2009, p.115). The atrocities committed to Vietnamese civilians by US-American soldiers are widely compared to the holocaust committed by Nazi Germany (Lawrence, 2008, p. 159).

For Nick Ut, this morning is just as many mornings in the war. A local village has been bombed with napalm bombs, there are dead bodies, fleeing villagers and a lot of pain and misery. Nick, holding his camera ready, walks on a highway with his colleagues and suddenly, he sees them.

A group of children, horribly burned by napalm, running crying towards him while US army soldiers and journalists walk quietly besides them, minding their own business. Nick lifts his camera, his powerful tool, and takes photos, one after the other, before he runs towards the children to carry out first aid. The photo that he took of the fleeing children this morning will win the Pulitzer price and plays an important role in the anti-war movement. It narrates the cruelties that are committed by the US-troops to Vietnamese citizens and a good example of the strong appeal that imagery has on the minds of people.

But the photo almost didn’t get published. Horst Faas, a German journalist, stationed in Saigon at the time, mobilized all his contacts to get the photo out of Vietnam and published. Associated Press was very critical of publishing a photo of a naked girl, but Faas directly realized the strong effect that publishing such a photo would have on public opinion worldwide. He knew, that this photo could have major contributions of ending this war. Horst Faas, working for Associated Press in Saigon, was also Nick Ut’s mentor and encouraged him to document the war in Vietnam for Associated Press. Horst Faas lend Nick and other young Vietnamese photography talents camera equipment and helped tremendously to get their work published. Apart from his role as recruiting young talents, Horst Faas also photographed and his photos are just as famous as Nick Ut’s “Accidental Napalm” is. The photos by Horst Faas are considered some of the best photos that were shot during the Vietnam war. Considering his role as a supporter for young Vietnamese talents and Faas’ journalistic impact by taking and publishing world-class photos of the war, one can say that Horst Faas was a central figure in shaping the photographic narrative that was told about the Vietnam war by media worldwide. Therefore, the question arises:

What are the uses of narrative in the photographic work of Horst Faas’ documentation of the Vietnam war?

To answer this question, I have selected four iconic photos, taken by Horst Faas between 1964 and 1971. Narrative refers to the succession of events, real of fictitious, that are the subjects of the discourse and has temporality (Casadei, 2015, p.30). But “photographic image stops, holds, fixes, immobilizes, highlights and separates duration, capturing a single moment of it” (Dubois, 1993, p.161). As “the flow, the race, the time has no validity in photography’s point of view”, photography is a figure without duration (Dubois, 1993, p.163). Never the less, we, the viewers of images constructs the temporality of images, by putting them into a context, into a historical frame through which we interpret them and their narratives (Stocchetti & Kukkonen, p.30). Consequently, the photojournalistic narrative says something about who looks at the picture

It is widely argued which impact the media had on the outcome of the Second Indo-China war, also known as the Vietnam war (Bradley, 2009; Griffin, 2010; Lewy, 1980). Horst Faas himself once said in an interview in 1997: “I don’t think we influenced the war at any time […] I don’t think we helped to win it or helped to lose it. We didn’t work on the outcome of the war.” However, he said that documenting a war is better than not documenting a war (Vitello, 2012). The control of narratives is key in establishing power relations and legitimizing the power of an authority. Controlling the mediazation of reality and the stories that are told about reality is part of it (Stocchetti & Kukkonen, p.16). Governments and political or economic interests work conscientiously to control, channel, limit, or delay image production and circulation that influences opposing narratives of war (Griffin, 2010, p.8).

Picture 1 – War is Hell

In the example of the Vietnam war, journalists challenged the narrative that was communicated by the US-army of brave man that defend the free world order in Asia (Griffin, 2010). This photo, taken on June 18, 1965 by Horst Faas challenges this narrative. The soldier, maybe 18-22 years old, is looking with a light smile into the camera. On a band around his helmet, it is written war is hell. Images that are communicated without the context, out of their historical, empirical linkage with agents, interests, media, circumstances, times and spaces, etc., stand for nothing, like a jellyfish taken out of the ocean or a snowflake taken from the air before it lands on the ground (Stocchetti & Kukkonen, 2011, p.30). When understanding the narrative of images, it is crucially important

to be familiar with the context of them. This photo portrays the feelings of thousands of US-American soldiers and the situation they found themselves in. Many were just fresh out of high school and have never been to a foreign country, let alone another US-state, before. Completely opposing the narrative of brave, experienced fighters, this photo shows the misery of a young man in hell. Seen in the context of young men that fight a war which can’t be won, the social establishment of the photograph is a cultural icon, a narrative maker of collective memory (Griffin, 2010, p.8). In addition to that, the narrative of the photo amplified the American sympathy with US army soldiers who seemed caught in a war for which national commitment was faltering (Oliver, 2006). American Television, which communicates a narrative through its implemented temporality, can be seen as a stream of under selected images, each of which cancels its predecessor. Photographs like this one on the contrary, are a “privileged moment”, turned into a slim object that one can keep and look at again (Sontag, 2010).

Picture 2 – Women and children crouch in muddy water

According to Oliver (2006), the American public had greater sympathy with US army soldiers than with Vietnamese civilians, even though pictures such as the one below was published. Horst Faas took this photo on January 1st, 1966, when the GI-unit, that he joined for a patrol was attacked by North Vietnamese forces. The photo’s main character are the woman and the girl in the front, they are in focus, hiding in the muddy water. Behind them, is another woman and her baby, and even further behind are soldiers. The narrative of the photo shows the suffering of Vietnamese civilians, who have worried faces. They are brought to the center of the image, as if the photographer wanted to show the victims of the war as being the Vietnamese civilians. In contrast to them are the soldiers in the background who are unfocused and who’s faces aren’t visible, hidden by grass. The framing of the image deliberately excludes the American soldiers and includes the suffering of the Vietnamese villagers. Images as such offer viscerally exciting and voyeuristic glimpses into theaters of violence that, for most viewers, are alien to everyday experience (Taylor, 1998). Images are alternative strategies for the competition over the distribution of values in society and independent war photography challenges the narratives that are communicated by dominant powers (Butler, 2009). This dynamic of images is quite independently of the nature of the political regime in which images are taken and shared (Stocchetti & Kukkonen, 2011, p. 33). But even in democratic countries, such as the USA, reporters and photographers who attempted to publish pictures of victimized Vietnamese civilians in the late 1960s and 1970s met resistance from the mainstream US media and were even blacklisted or banned (Griffin, 2010).

Picture 3 – Father holding dead child

When accompanying American and South Vietnamese soldiers, Horst Faas often documented atrocities that were committed to civilians during the war. In the photo below, taken on March 19, 1964, a father holds his dead child, which was killed when South Vietnamese government forces pursued gorillas into a village near the Cambodian border. The structure of the photo communicates the narrative of a helpless victim against an overpowered enemy. Soldiers, sitting on a heavily armed vehicle are looking down on the father. They are above the cruelty, they are safe. The meaning of the photo relates to the general patterns it reveals about what war is. But the meaning is not simply located in the photo, it is produced by the observer and his or her assumptions, worldviews and prior narratives (Mayer, 2014, p.10). An extreme passion is captured in the photo that takes urgent claims on the viewer’s attention (Brothers, 1997). The narrative of the South Vietnamese troops, which were supported by the USA, as the overpowering force that kills children creates an alternative dimension of the political. The interpersonal and the intersubjective quickly turns into a matter directly affecting the competition for the distribution of values in society (Stocchetti & Kukkonen, 2011, p. 33). Those values might be human rights or democracy, for US-American viewers, and the space of uncertainty that the narrative of such a photo creates, invites for a reconsideration of the Vietnam war and its political aims. The angle from which the photo is taken and how it is framed, contribute greatly to this interpretation, as the military vehicle is visible as this big, overwhelming mass, against which the father and his dead son appear small and helpless.

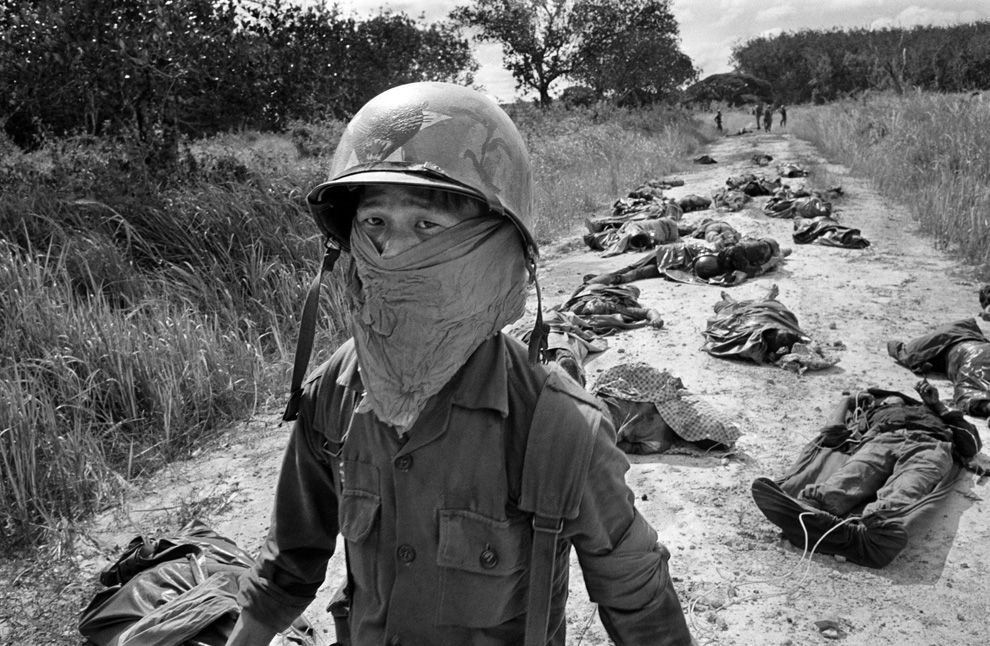

Picture 4 – Dead Bodies

As the Vietnam war went on, more and more people were killed and the public opinion in the United States changed, opposing the war and American involvement in it. A reason for this was the rising number of American soldiers that were killed in the war and the media presentation of those losses (Griffin, 2010). Horst Faas documented this process with photos as the one below which was taken on November 27, 1965. Dead bodies are laying near a rubber plantation in South Vietnam before they are transported to be properly buried. In the front stands a South Vietnamese soldier, who looks in the camera and has his face covered against the rotting smell. The viewer is forced into a situation in which interpretation of the photo’s narrative is necessary but at the same time arbitrary and therefore ambiguous (Stocchetti & Kukkonen, p. 30). From an American perspective, the narrative of the photo describes the hopelessness of the war. The view of the man in the front is in despair, while dead bodies cover the dirt road behind him.

Horst Faas’ work encompasses many more than those photos, for which he won the Pulitzer Price twice. The communicated narratives tell stories about the people of the war. About suffering civilians, about young Americans killing and dying in a war initiated by white, old men, such as Richard Nixon or Lindon B. Johnson and about the cruelties of war. But the willingness to accept the premises of Faas‘ communicated narratives depends on the viewers of his images to evaluate the truth of narrative in terms of its precise correspondence with the real world. To grasp those narratives, viewers need to open their minds up and let go of a photo’s conformity with their general conceptions about the way the world works (Mayer, 2014, p.10). Photographs act on us and the analyzed photos communicate the suffering of individuals in war in such a way that viewers were prompted, and are still, to alter their political assessment of war (Butler, 2009, p.68). Even though, it is argued whether war photographs communicate a narrative, they definitely capture atrocities around which viewers construct narratives (Butler, 2009; Casadei, 2015; Dubois, 1993). Faas’ photos are known around the whole world and shape the memory of millions of people by documenting and telling the war in Vietnam.

References

Bradley, M. (2009). Vietnam at war. Oxford University Press.

Brothers, C. (1997). War and Photography: A Cultural History. London: Routledge.

Butler, J. (2009). Frames of War: When Is Life Grievable?. London: Verso.

Casadei, E. B. (2015). Can still images tell stories? Symptom and temporality in photojournalism narrative theory. Brazilian Journalism Research, 11(1), 28-43.doi:10.25200/bjr.v11n1.2015.804

Dubois, P. (1993). O ato fotográfico e outros ensaios. Campinas: Papirus.

Griffin, M. (2010). Media images of war. Media, War & Conflict, 3(1), 7–41. doi:10.1177/1750635210356813

Lawrence, M. A. (2008). The Vietnam War: A Concise International History. Oxford University Press.

Lewy, G. (1980). America in vietnam (Ser. A galaxy book, gb 601). Oxford University Press.

Mayer, F. (2014). Narrative politics : stories and collective. Oxford University Press.

Oliver, K. (2006) The My Lai Massacre in American History and Memory. Manchester University Press.

Sen. (2018, November 20). After Hell and Hollywood, Nick Ut basks in peace. VN Express. https://e.vnexpress.net/news/travel-life/after-hell-and-hollywood-nick-ut-basks-in-peace-3835521.html

Sontag, S. (2010). On photography. London: Penguin Books Ltd.

Spector, R. H. (2020). Vietnam War. In Encyclopaedia Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/event/Vietnam-War/The-Diem-regime-and-the-Viet-Cong

Stocchetti, M., and Kukkonen, K. (Eds.). (2011). Images in use: Towards the critical analysis of visual communication.

Taylor, J. (1998) Body Horror: Photojournalism, Catastrophe and War. New York: New York University Press.

Vitello, P. (2012, March 12). Horst Faas, Photographer Who Showed Horrors of War, Dies at 79. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2012/05/13/world/asia/horst-faas-vietnam-war-photographer-dies-at-79.html

Zelizer, B. (2010). About to Die: How News Images Move the Public. Oxford University Press.